Consistency in the Basics – Part 2

10.12.18

With Basics You Can Fight

“If one is proficient in Kihon Happo, San Shin and Muto Dori, they can fight.”

This quote, attributed to Nagato Sensei, emphasizes that good basics are key to our ability to fight.

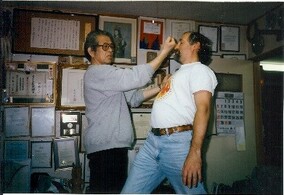

Taken the day after I passed the Sakki test. Interesting Bujinkan trivia; mounted on the wall behind us is Ishizuka Sensei’s Katana that Soke broke in half with a Hanbo.

Part One, raised the question: If basics are so important, why are they no longer being emphasized in training in Japan? We looked at training in the Bujinkan over the preceding four decades and concluded that this is a relatively new phenomenon which may only apply to some of the senior-most [pl1] Japanese Dai-Shihan. Basics were consistently taught by Soke and his original senior Japanese Shihan from the 1970s through the 1990s. By the 2000s, Soke had shifted from teaching basics to more conceptually themed training and advanced/exotic weapons. However, he instructed the Japanese Shihan to emphasize basics in their dojo. A few Shihan continued to teach basics and a few chose to teach the theme of the year or their interpretations of Soke’s movement instead. The latter was true especially for Gaijin Shihan who visited Japan periodically (but did not live there full time). The senior-most Shihan sometimes taught the current theme in the context of the basics, providing a framework to understand the esoteric concepts of the year’s theme. However, there is a third group of Japanese Shihan [pl2] who have consistently taught basics from the first day they opened their dojo until today. That group consists of the younger Japanese Shihan (you could call them the 3rd Generation Shihan) and several of the long-time Gaijin residents that have their own dojo. Basics are alive and well in Japan. You just have to broaden your training experience to find those dojo(s) that offer it. [

Note: In Part 1 I explained Gen 1, 2 and 3. To recap, I call the senior-most Dai-Shihan who started with Soke in the early 70s the First Generation or Gen 1. Noguchi Sensei is a Gen 1. Students of Gen 1 who become Shihan are who I call the Second Generation or Gen 2. Nagase Sensei is an example of a Gen 2 since he was a student of Noguchi Sensei. Students of Gen 2 who become Shihan I call Gen 3, etc. Tezuka Sensei is an example of a Gen 3 Shihan as he started with Nakadai Sensei who was a student of Noguchi Sensei’s.]

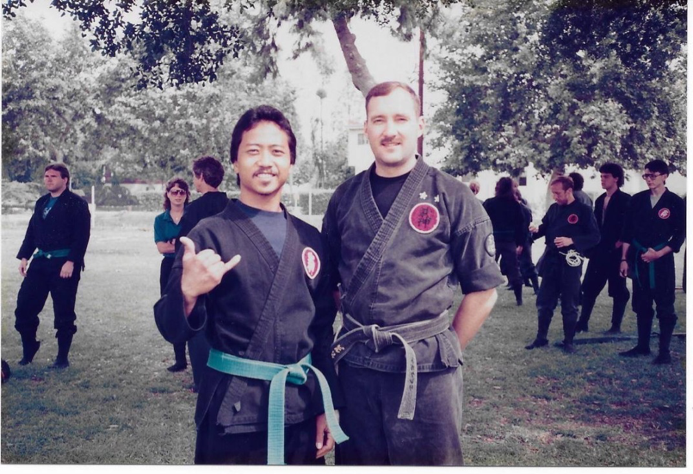

LA TaiKai 1988: Author with Robert Abila, or as Soke called him, Hawaii Boy

Now in Part 2 let us look at the “Cycle of Life” to frame how Soke has taught students in the Bujinkan over the last 40+ years.

I remember when Soke first came to America and Europe in the early 1980s. At those early seminars, he would tell us that we were like brand new babies, Bujinkan infants just learning to crawl. In the 1990s, Soke called us toddlers, now able to stand up and walk, but our Taijutsu was still wobbly. In the 2000s, we became teenagers, then young adults. Today Soke calls us grown, mature adults. Each stage corresponds to training we received from Soke. In the infant and toddler phases we were trying to learn all the basic movements with some emphasis on Henka. Rolling, punching, kicking, blocking, Ichimonji, etc. The San Shin, Kihon Happo and the Tenchijin book were our training materials. By the teenage phase, we might have had about 10 years of training under our belts, yet the focus was on basics and henka of the basics. The end of the teenage and the beginning of the young adult phases can be marked by the Sakki test. Once you pass you are recognized, not only with the rank of Godan, but also with one of the only official Japanese martial arts titles: Shidoshi (licensed instructor). As “young adults”, and upon passing the Sakki test we may open up a dojo and begin teaching while still training as senior students of Soke. As we earned rank over the following years, we ostensibly gain that seasoning and adult maturity that comes through many long years of consistent training in the basics. On average, after about 20 years of training in the Bujinkan we were at the Judan level or higher and considered mature adults in Soke’s eyes. Today, Soke only teaches for the 15th dans. says he is only teaching for the 15th dans.

When did your Bujinkan “life” begin? Whether during the 1980s infant phase, the 1990s toddler phase, or the 2000s teen/young adult phase, most likely you developed a solid, strong foundation by learning and practicing the basics relentlessly for at least a few years. Many senior people I’ve met it believe passing the Sakki test signifies they no longer need to practice basics. In fact, one rather infamous senior Gaijin who lived in Japan used to say, “Pass the Godan test and you have a license to forget.” And I also remember Soke saying on a number of occasions that starting at the Godan level, students should start to break the forms and focus more on Henka and then after Judan the student should work to become formless in their movement. In today’s training, Soke emphasizes no power, and no form, to control the opponent. He also says control your opponent but do not allow yourself to be controlled. [Note: This is the duality of control paradox that I have written and talked about on a number of occasions and am teaching at my seminars.] Many times he has said, “showing your form (or power) and you can be defeated.” What does “no form” mean exactly? For many it was seen as reinforcement to not practice the basic waza or kata. But is this really what Soke meant? If so, why does he keep telling the younger Japanese Shihan to teach and study only the kata in their dojo. One of the younger Shihan told me once that he would only teach Soke’s movement to other 15th dans, and not to junior students. Meanwhile, Gaijin who visit Japan only see or hear “no form, no power”. They may go back to their own countries with the idea that Soke does not want them to practice or teach basics anymore. Worse, they may get the idea that they should train to imitate Soke’s movement. Most of us know how unrealistic that is. Yet there are people who return to their students and teach how they saw Soke moving and call it the “training theme for the year,” without providing further context. But, and it’s a big but…. Soke has said numerous times, “Don’t move like me. I move like an old man. Move like yourselves.” This may sound like common sense, but some people don’t get it. Could be the lack of translation that this is misunderstood, or from a sense of duty/loyalty to not vary what Soke shows us. Or they only train with Soke and not the other Japanese Shihan. Whatever the reason, it doesn’t seem to be understood by many who visit Japan.

I visited Japan for training frequently over the last four decades. When I would return from a trip, invariably students would ask me to “show us what you learned in Japan.” I would give a blank stare, look confused and say something like, “I don’t know what I learned, it was all a blur, I am suffering from training overload, my notes don’t make sense.” Sound familiar? I would shrug and teach class as usual. I always started class with Kihon Happo, San Shin, Ukemi and some Muto Dori. I would focus on the basics and eventually some bit of my Japan training experience would come out and we would develop that. Over time I would be remember more. It usually took 6 to 9 months until I felt I had recalled most of my Japan training. Once I felt that, it was time to plan my next trip. This illustrates how I utilize the basics to trigger the visionary concepts that Soke is teaching. Using the basics as a training framework allows us to see the connection to advanced techniques. If we practice the basics long enough and often enough to get to a Mushin state of no-mind when actively doing them so they are instinctual, then and maybe only then, can we connect the dots leading to what Soke and the senior Japanese Dai-Shihan are trying to teach us.

Senior Japanese stay grounded in the basics. After moving back to Japan in 2015, I heard some senior Japanese complain that Gaijin don’t know basics. Yet, as previously noted, they were not teaching them to Gaijin. As a senior Dai-Shihan and a Gaijin, I had to own that. When Soke was late to Sunday class, one of the senior Japanese would occasionally ask me to start class. So until Soke arrived I would warm up the class on those Sundays with my version of the San Shin and Kihon Happo. Many students would follow along, but there were a number of visiting senior Gaijin who would stand in the back or behind their students and just watch. When Soke arrived, he would comment about me teaching basics and laugh and say something like, “Good, Shogun is teaching.” But Soke also noticed who was NOT training, who was just standing and watching. Sometimes the Japanese senior Dai-Shihan would tell Soke who wasn’t training or how bad the Gaijin were at basics. It came as no surprise to many of us locals when in 2016 Soke started saying that the 15th dan must perform the Kihon Happo and the San Shin correctly and on command. The actual Japanese word Soke used was Kampeki (perfect), meaning they must demonstrate these basics perfectly. After Soke’s comments my warm-up sessions became much more popular. I requested feedback from all three of the Senior Japanese Dai-Shihan concerning my form and how I taught the basics. Noguchi-sensei laughed and said they were great. Nagato-sensei said they looked fine, but he wanted to know why I was teaching basics and not “cool stuff.” When I explained, he said okay great![pl1] Senno-sensei gave me a small bit of advice on Ku no waza related to hand placement. He suggested what I showed was the way we used to do it, but it had changed slightly over time. I asked if he knew why and in typical Senno-sensei fashion, he sucked his teeth, shook his head and said he didn’t really know. Good enough for me though, so I changed. He was kind of amazed when I taught the San Shin to class a few minutes later, that I could alter my hand placement that easily. I told him later, since I am functioning in a Ri state of Mushin when doing the basics, I have plenty of brain reserve to think (Shu) about making that one little hand change. With enough practice that hand change will move from a Shu state to Ha state and finally to Ri. it moves to Ha. Senno Sensei got a really big grin on his face when he understood what I had said. He really liked that idea of Shu-Ha-R as a way to explain the stages of learning we go through.

December 2018: Soke’s birthday party. The last time the author saw Senno Sensei before he passed away in early 2019.

A final note before we close out Part Two. Take a look again at Nagato Dai-Shihan’s comment at the top of the article. Do you agree with his statement, that with good basics you can fight?

In Part Three we continue to explore, “How do we consistently train in basics, yet grow our abilities in the martial arts?” We’ll look at the Japanese concept of Shu-Ha-Ri as a learning model that blends consistent basics with consistent learning growth in the martial arts.

About the author:

Dai-Shihan Legare began training in the Bujinkan in 1977 in Aomori, Japan. He hosted Hatsumi Soke for three US Taikai (1993,1998,2001), is the recipient of four Bujinkan Gold Dragon Awards, was awarded menkyo kaiden in Shinkengata (real combat fighting), received the Bufu Ikkan lifetime achievement award for martial arts excellence, and is the only recipient of the BuyuSho award from Hatsumi Soke recognizing his benevolent warrior spirit. Additionally, he is a combat veteran with more than 44 years of combined service in the USMC and the Department of Defense. He is married to Joanne Legare, also a Dai-Shihan in the Bujinkan and recipient of a Gold Dragon Award. Phil and Joanne lived in Japan off and on for many years and now reside in Hawaii.