Consistency in the Basics – Part 1

10.12.18

Consistency in the Basics – Part 1

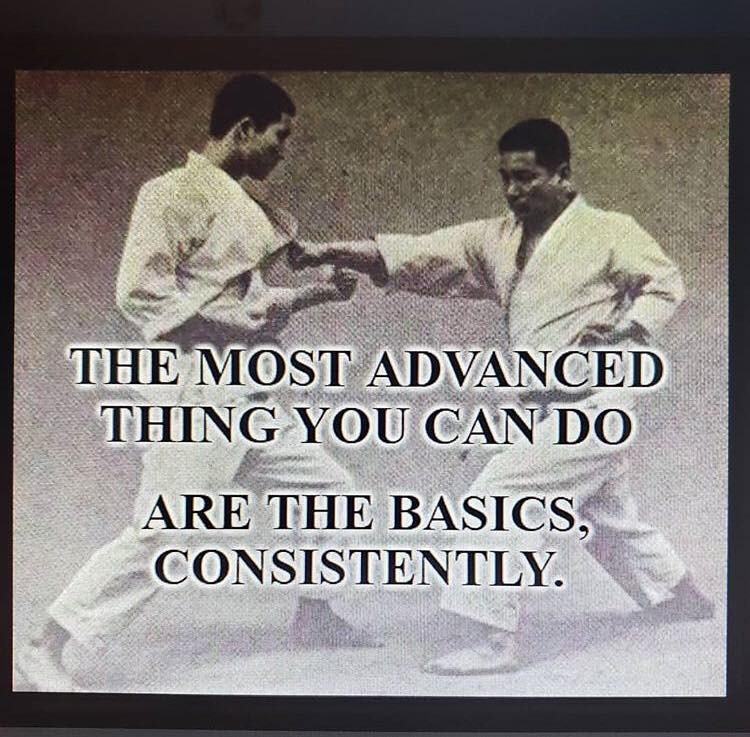

This meme about the importance of basics is trending now on social media. Aristotle’s famous quote, that Excellence is a Habit (not a single act), is Westerners way of stating this meme’s message. I agree with the meme and Aristotle, and thought this an opportune time to write again about this topic that is near and dear to my heart. I have previously written blog articles for the takaseigi.com website concerning the importance of developing a strong, balanced structure and a solid foundation through the practice of the basic fundamentals of Bujinkan Budo Taijutsu. This solid foundation provides the grounding and solidness and base strength which the student builds upon over the life of their training. Just like a house cannot withstand a hurricane or typhoon winds without a really solid foundation, the student cannot grow in martial arts ability and understanding without a solid foundation to serve as a strong base upon which to build. Seeing this meme and some of the comments posted about it reminds me that no matter how much we talk about how important basics are to a martial artist’s growth, there is some nagging thought that basics are just for beginners. And dare I say, our martial arts training encourages us to think this way.

Martial arts conditions us to receive recognition when we excel, or make progress in our training. Once we are awarded a new belt color or rank, we are then told that we are ready for more advanced training. Depending on the teacher, we might be given new rank’s requirements to work on, allowed to attend the advanced class, or encouraged to make that first trip to Japan to train with Soke.

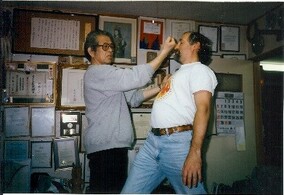

(Author making tea for Fukuda Sensei at his mountain dojo in Gonohe, Japan, 1978.)

And then there is Japan training. In my opinion, training in Japan these days is more about inspiration and socializing and less about skill-building. At least that is my perception of training with the senior most Japanese Dai-Shihan to include Soke. Training with either Soke or the top tier Dai-Shihan is always at a very high level. Soke will say during class that he is teaching to/for the 15th dan or Dai-Shihan now. We don’t see basics at Soke’s or the top tier Japanese Dai-Shihan training. They know that the multitudes of visiting foreign students didn’t fly all the way to Japan to see basics. Most are coming over on an annual training pilgrimage. First time visits are usually the start of what becomes an annual pilgrimage. And for some, that first trip turns into a decision to move to Japan to be close to training year-round. People come to Japan to be inspired, and Soke never disappoints. He shows really cool stuff that looks impossible to do and we become inspired to train harder and to keep coming back to Japan.

Are basics taught in Japan anymore? I am happy to say that basics are alive and well in Japan, but you have to know where to find them being taught. I have experienced great basic training at almost all of the Gen 2 and Gen 3 Japanese Shidoshi/Shihans’ dojo, as well as at several of the long-time resident Gaijin dojo. For clarification, when I say Gen 2 or Gen 3, what I am describing are those Shidoshi/Shihan who had been students of the original generation (Gen 1) of Shidoshi under Hatsumi Soke. People like Ishizuka and Noguchi are examples of what I call the original Gen 1 of Soke’s students who went onto became Shidoshi. An example of Gen 2 would be Nagase and Nakadai, who were Noguchi Sensei’s students starting in the mid-80s. An example of a Gen 3 would be Tezuka who was Nakadai Sensei’s student starting in the late 90s. Most, if not all of these Gen 2 and 3 Japanese Shihan teach the basics and kata forms as part of their normal dojo training. If you attend one of their training sessions you will note that there are more Japanese there than Gaijin. That is a key indicator that the training is going to be more skill-building in nature (which I find to be almost as inspirational as Soke’s training). You can expect to do a full set of warm ups at the start of class. These warm ups will likely include: Kihon Happo, San Shin, Ukemi, and Muto Dori. My advice to people visiting Japan (regardless of rank) is to attend Soke’s and several of the top Dai-Shihan classes to get your inspiration fix and work on very high-level training concepts. But also visit a few of the younger Japanese Shihan to see unfiltered basics and polish your own understanding of them. I also recommend training with some of the long-term resident Gaijin to see how they blend the current training themes in Japan with their many years of experience living and training in Japan. Warning, be prepared to receive honest feedback on your movement and technical skills from the younger Japanese Shihan and especially from the Gaijin. That feedback is key for proper growth and understanding of this art, especially for those who live in other countries who may not have a really experienced senior teacher to work with on a regular basis, and/or only visit Japan occasionally for training.

I won’t mention too many names in this article to avoid the appearance of having favorites (which admittedly I do), but if you subscribe to the takaseigi.com website you will see who I predominantly film for the site. And if you follow me on the TakaSeigi, Hawaii Bujinkan or Yokota Bujinkan Facebook pages or my Instagram DaimondPhil19, you will see who I normally train with when in Japan. I can provide my suggestions if you ask in a private message. I am also in the process of setting up a podcast for training and will definitely get into more detail on training in Japan in that space.

A Little Bujinkan Training History

Four decades ago, Bujinkan training in Japan consisted of Soke’s regular/basics classes and the Shidoshi Sunday class. Anyone could attend the regular/basics classes, but you had to have passed the Sakki (5th dan) test to attend the Shidoshi Sunday class. At that time, the Japanese were required to pass the Sakki test and be awarded the title of Shidoshi (teacher) before being allowed to teach class on their own. By the late 70s, a few of the Japanese had passed the Sakki test and started teaching their own Bujinkan classes. These were a few of the Gen 1s. By the mid-80s, this small number of Japanese Shidoshi had grown significantly. Besides Soke’s classes, one could find training at 7-8 different Japanese Shidoshi dojo within an hour or so of Noda. As the “Ninja Boom” hit the world in the mid-late 80s, a demand signal for more Bujinkan instructors and classes in Noda became evident as more and more people went to Japan to seek out training in Ninpo Taijutsu. Having more training choices AND having the opportunity to train regularly with one of the original Japanese Shidoshi was a major reason many of those early Gaijin travelers decided to move to Japan. No one back then could predict how popular Bujinkan training and Hatsumi Soke would become back then, but getting in on the ground floor (so to speak) was prophetic.

Training back then in Japan was somewhat secretive and difficult to find. There was no google or fb to reach out to for info. Getting around Japan was much more difficult back then for the non-Japanese speaking foreigner and there were no high-speed trains back then. In 1977, I asked my original Bujinkan teacher Fukuda Sensei (pictured above), should I go train with Hatsumi? And where was the Noda Hombu exactly? He laughed and told me it was a 13-hour train ride away, near Tokyo and I could go if I wanted to. At that time, I decided it was more cost and time effective to train with Fukuda Sensei there in Aomori. Hand drawn maps with dojo locations were gold back then too. We basically made our own map/direction notes for ourselves. I remember once hearing OB (Mark Obrien) say he was going to make a fortune selling his hand drawn maps of the training locations around the Noda area to visiting students. His get rich quick scheme was short lived as more and more people went to Japan and started making their own connections with the Gen 1 instructors.

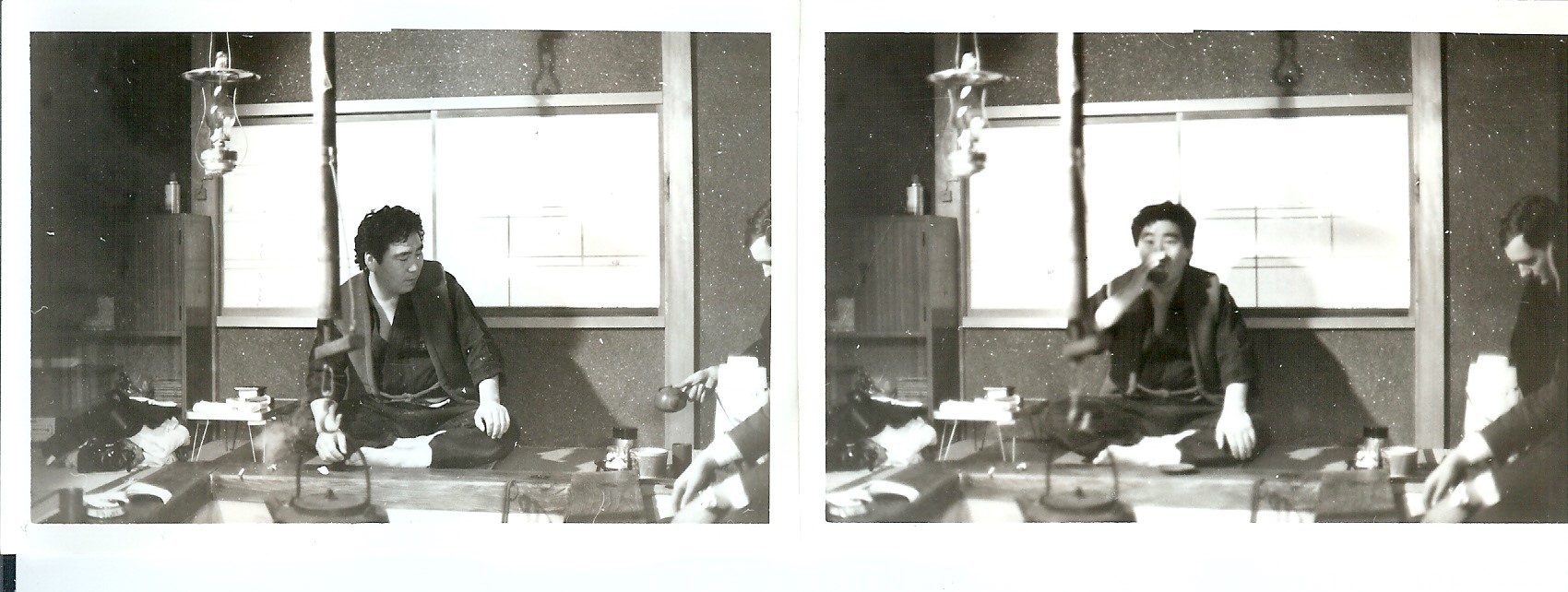

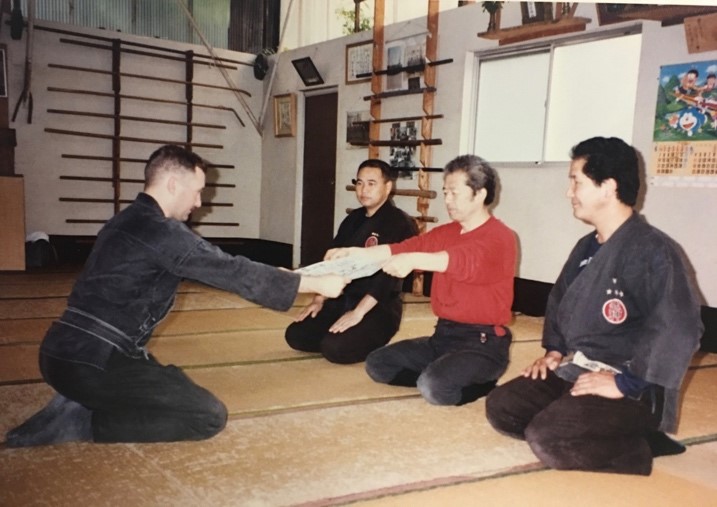

(Author receiving Menkyou from Hatsumi Soke after passing the Sakki test in March 1989. This was at the Shidoshi Sunday class with Ishizuka Sensei and Manaka Sensei (retired) looking on.)

By the 90s, another generation of Japanese Shidoshi were ready to launch into teaching. These were the Gen 2s who were the senior students of the original Shidoshi (Gen 1s). This crop of instructors tripled the number of instructors within an hour or two of Noda and spread out to a few other places in Japan too, such as Tokyo and Osaka.

Training in Japan up to this point (70s-90s) was basics-oriented training. Even in the Shidoshi Sunday classes it was all about the basics of the various Ryu-ha, including basics and Henka of various weapons. Every class started with various combinations of Kihon Happo, San Shin and Ukemi. One of the Gen 1s liked to run through the entire Tenchijin for the first 30 minutes of class. Another spent a lot of time reviewing various rolls and falls. Still another would warm up with basics of bo and sword. The theme of training for approximately 30 years was basics of all the Ryu-ha, to include Ukemi, (falling/rolling/avoidance), JuTaijutsu (grappling/throwing), DakenTaijutsu (striking), Bodogu (weapons), and TaiSabaki (natural movement). The Tenchijin Raku no Maki pretty much covers all of the basics of training (minus weapons). The Kihon Happo and Sanshin were created as a way to teach basic structure, with basic blocks and strikes. And a bonus being the San Shin and part of the Kihon Happo (Koshi Sampo-3 Kamae) movements could be practiced solo.

Something happened around the time of the early 2000s to training. The training in Japan became more “advanced,” for lack of a better word. Soke changed from teaching basic themes to cool/visionary concepts (ex. Rokkon Shogo, Juppo Sesho, Kuki Taisho, Kanami, etc.) and lots of advanced weaponry (ex. Tsuguri, NagaMaki, Shikomi Zue, Tessen, Kunai, etc.), and even interesting clothing (ex. Hakama and Haori). The training taught by the Japanese Shihan during that time was (mostly) their interpretation of whatever Soke was teaching at that moment. After moving back to Japan in 2003, I would hear a number of the Japanese senior Shihan complain that the Gaijin were not good at basics anymore (“they suck” may have been the words I heard the most often). Yet, these same senior Shihan rarely corrected or taught visiting Gaijin proper basics. By and large they would try to teach and explain what Soke was teaching. However, there was one of the Gen 1s who was always happy to humble visiting Gaijin (me included) with a brutal critique of our performance of the Tenchijin Raku no Maki. I found those occasions, where I got truthful feedback, to be keynotes of my own training growth over many years.

At the end of year Daikomyosai (DKMYS) 2007, at Shimizu Koen, Soke made open comments that we need to re-learn the basics. I think the “we” meant everyone, not just the Gaijin. He had Noguchi Sensei do the San Shin and he told us to practice Noguchi’s version for the rest of training that day. Soke told the senior Japanese Shihan they were to continue teaching Gyokko Ryu basics going into the new year (2008). Gyokko Ryu basics had been the theme during 2007, and it changed in 2008, but only Soke would teach the new theme. This went on for a couple of years, but still the basics were only really emphasized in the Gen 2 and Gen 3 Japanese dojos. Basics have really not been taught consistently by the senior Japanese (Gen 1), for various reasons, since the 90s.

Fast forward to today. Soke will tell you he is only teaching to the Dai-Shihan. So good luck!

In Part 2 we will continue the question, “How do we consistently train in basics, yet grow our abilities in the martial arts?” We will look for clues to this connection between basics and advancement in the cycle of life phases that Soke used to describe Bujinkan students; starting in the 80s as infants, and going until the 2000s when he proclaimed us to be adults.

About the author:

Dai-Shihan Legare began training in the Bujinkan in 1977 in Aomori, Japan. He hosted Hatsumi Soke for three US Taikai (93, 98, 01), is the recipient of 4 Bujinkan Gold Dragon Awards, was awarded menkyo kaiden in Shinkengata (real combat fighting), received the Bufu Ikkan lifetime achievement award for martial arts excellence, and is the only recipient of the BuyuSho award from Hatsumi Soke recognizing his benevolent warrior spirit. Additionally, he is a combat veteran with more than 44 years of combined service in the USMC and the Department of Defense. Joanne Legare, Phil’s wife and also a Dai-Shihan in the Bujinkan often co-teaches at his seminars, is also the recipient of a Gold Dragon Award. Phil and Joanne lived in Japan off and on for many years. Phil is recently retired and both now reside in Hawaii.